Inviting contemplative practice into the scientific process.

As humans, we have long sought to understand the nature of reality and our place in it as conscious beings.

When considering the nature of reality, how do we know what is true?

Humans have pursued many paths to truth- various forms of scientific inquiry, philosophy, formal logic, religion and metaphysics, among others. Each of these attempts to create a formal system for understanding the nature of reality that is internally consistent and complete, and yet each finds limitations that cannot be explained.

One of the oldest forms of knowledge creation is inductivism, which is an approach to knowledge that stems from producing theories about the nature of reality from our past experience. "Because this happened in the past, it will happen like this in the future." But inductivism is limited by its explanatory power. For thousands of years people knew that apples fell from trees, but that knowledge did not allow them to understand how to fly. It wasn't until Newton came along and proposed an explanation for how gravity worked that people were able to figure out how to actually fly based on this newfound understanding.

The physicist David Deutsch says that all scientific theories are explanations about the world and how things work. The key to the scientific method is that our explanations about reality can be improved through ideation, criticism, and testing. Thus the field of science becomes a search for good explanations.

Karl Popper, a philosopher of science, states that all observations about reality are theories based on our interpretation of reality, and thus inherently limited and fallible.

For thousands of years, people looked up at the night sky and wanted to better understand the world in which they lived. They observed patterns, formed connections between ideas, and tested new theories.

Before the scientific revolution in the 1700-1800's, new theories about the nature of reality were usually rejected outright, or even worse, those promoting them were punished, killed, or ostracized from the community. The word of authorities was meant to preserve institutions and political and religious powers. It was only with the scientific revolution that a tradition of criticism and testing started to pervade the wider culture.

The scientific revolution opened up a search for good explanations, explanations that are testable, reproducible, and hold up to criticism. A good explanation is one that doesn't introduce contradictions, is repeatable, and hard to vary.

The growth and promotion of science is based on the principle that explanations about reality are no longer good explanations when they have been refuted by experiment or new knowledge. This method of criticism, correcting errors and misconceptions when they occur, and continuing the search for a better explanation have led to the greatest gifts that science has offered the modern world.

Empiricism is a form of scientific inquiry based on sensory experience and the rise of testable experiments based on the material world. Empirical science proceeds by experimentation to examine the material world, building testable experiments to find additional data and information to further support or disprove previous explanations. This method of science has given rise to most of the innovations of the modern world, from computers, to antibiotics, and the infinite variety of other inventions.

The problem with empirical science is it requires a clear separation of subject and object. The subject is a passive observer defining reality in a purely objective fashion.

Quantum mechanics sets limits on empirical science with the discover that the separation of subject and object is no longer possible. Quantum theory explains that the nature of reality is a vast, complex system in which there is no true thing, no true separation, and that space-time is an energetic field which forms the fabric of reality. According to this explanation there no solidity to material reality, that the 'world out there' is not separate from the observer, but the observer is intimately entangled in giving rise to their experience of the world.

Quantum theory leads us to hard problem of consciousness, if subjective consciousness is entangled with the nature of reality, how can we explain the subjective experience of consciousness? Empirical science can mechanistically explain the neural correlates of conscious experience, how the various electrical, chemical, and cellular mechanisms work to create our experience, but it fails to address the subjective experience of consciousness itself, the 'lived experience of being conscious.'

With quantum theory setting a hard limit on the reach of empirical science to explain the nature of reality, the question becomes where do we look to find good explanations for how consciousness fits into our understanding of the nature of reality. Is consciousness separate from the nature of reality? Is it an emergent property that arises from complex systems of non-living matter? Or is consciousness the background from which space-time, energy, and matter emerge?

Those are not easy questions and the answers to those do not lie within the domain of empirical scientific methods. Traditionally answers to these questions have come from philosophy, metaphysics, and spiritual traditions. As the scientific community is wrestling with these questions, they are opening the doors to contemplative practices to shed light on these questions, but they are also doing so in a way that upholds the principles of the scientific revolution.

As contemplative practices come to play a major role in our understanding of the nature of reality and our place in it as conscious beings, the most successful attempts will be those that provide good explanations about consciousness and its connection to the nature of reality. Good explanations are internally consistent, testable, reproducible, and hold up to criticism.

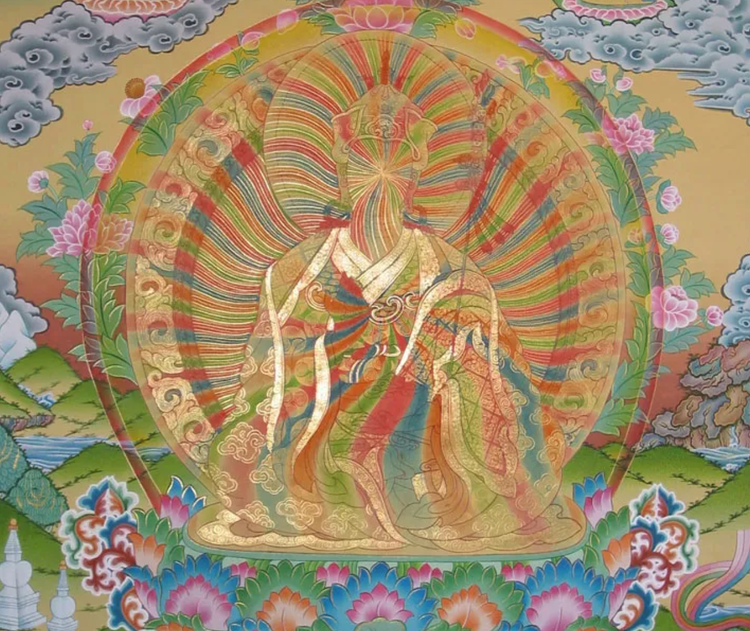

I believe the wisdom of the ancient practice traditions have major contributions to share in our understanding of the nature of reality. Over the next few weeks, I will be continuing to explore these questions from the perspectives of Mahamudra and Dzogchen, hoping to shed light on the nature of pure awareness and how the split to subject-object duality gives rise to our experience of the world. I hope to do so in a way that preserves the integrity of the insight into the nature of the mind that is the legacy of the Buddha's teachings, while also building connections to modern scientific explanations about the nature of reality.

Wish me luck, and I hope you join me on this contemplative inquiry!